IMMEDIACY AND HELMUT FEDERLE

Richard Shiff

In English, the terms medium and immediate are obviously related, not only etymologically, but logically. Mediums mediate. Mediums stand between things. But by standing between, they connect one element to another. What is connection, if not immediate? When two people face each other and converse, language is the medium; and so, in a different respect, is the air between them, which carries the sound.

The medium of drawing links what an artist observes, whether by eye or imagination, to its visual image. Among hand-oriented modes of representation, drawing, because it is so direct, is the most immediate of mediums. Drawing is both the language and the air. This is the experiential magic, the intimacy, of drawing, its double-sidedness of observation and image—hard to convey in a verbal medium, which relies on proper syntactical order.

The immediacy of drawing corresponds not only to moments of visual sensation but also to the thinking, the self-conscious awareness, that accompanies the organic flow of an active life. Consider that when a person draws, seeing and thinking exist integrated on the same sensory plane, the surface that bears the marks. When Helmut Federle draws, he lives this immediacy, with all its attendant risks of imperfection. A life of immediacy enters its next moment without knowledge of its own inadequacies.

Many of Federle’s works on paper—“drawings” by customary definition, even if “painted” with acrylic or watercolor—are technically complex, consisting of several layers of articulation. A watercolor titled Rain in the Mountains (1974)[1]

includes an element of collage that, by introducing a second level of paper cut into angular contouring, channels some of the liquid watercolor along its raised edge, creating graphic features that connote both mountainous elevations and conditions of precipitation. The flow of watercolor is a happenstance element, a microcosmic reflection of cosmic gravity within an image of natural forms, themselves once configured by gravity. A related, untitled work in acrylic (1977)[2] has several superimposed watery layers, with an angular motif—mountains again?—rendered less distinct by other configurations imposed upon it.

If immediacy is a concern, a question arises. Can such works, with their layers of pigment, be as definitively immediate as an untitled pencil drawing, simply linear (1979)[3]? The pencil drawing (imperfectly) mirrors triangular forms around a central vertical axis. It has the advantage, if it is one, of being more rudimentary in execution than the works in watercolor or acrylic. Another untitled work in pencil (1978)[4] arrays analogous triangular forms horizontally, now perhaps an abstraction of a mountain range. Embellishments appear: arcs between the triangles suggest gentle hills; segments of horizontal line in the lower register of the drawing suggest a landscape plane. Despite these representational possibilities, the artist’s imagination might have been centered on geometry and not land. The degree of ambiguous suggestiveness in Federle’s drawing reminds me of the connotative power and tactile sensitivity of early works on paper by Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich—two artists of abstract form who transcended the abstraction/representation divide.

Can an elaborate pencil drawing be as immediate as a simple one? It may be an irrelevant question. The distinction between complexity and simplicity has little to do with the type of immediacy perceived in Federle’s art—the direct contact that his works on paper establish between thought and sensation, sensation and thought. Consider another of his painted “drawings,” an untitled work in acrylic and pencil (1977)[5]. Like the configurations in Rain in the Mountains and several other examples from the 1970s, this image connotes a mountain range, with one or more elevations farther back, obscured by what lies in front, presumably closer to the position of the viewer. The penciled contour of the primary “mountain” is so heavily incised that it acquires a tactile edge. In contrast to the pencil line, the application of watery layers of acrylic generates a silvery atmosphere. An anomalous black form and three blue marks seem disengaged from the “scene,” like thoughts without a discernible cause, accidents of the senses or the mind. This combination of markings provokes speculation upon speculation—a layering of speculative thought to correspond to the material layering that comes naturally to the use of watercolor or acrylic on paper. Federle’s layers sustain sensory and cognitive immediacy despite their complexity.

A generalization: in Federle’s art, sensation comprises thought, and thought comprises sensation. His drawings and paintings are thought experiments, the sensations of thinking. The drawings are inchoate ruminations, speculations, musings, projections. They are happenings, events. They reflect thinking conducted with materials and forms rather than words and concepts.

Many Federle drawings remain untitled, but several in the group from the 1970s have designations that refer to mountains. Having been raised in a relatively remote area of eastern Switzerland, Federle knows mountains and their triumphs and dangers, their ups and downs. In Rain in the Mountains, rivulets of watercolor flow downward suggesting effects of the high-altitude climate. The watercolor Engadine with Mountains, Lake & Sun (1976)[6] has a descriptive title, but the forms are abstracted and symbolic: a blue triangle evokes “mountains,” a yellow oval evokes “lake,” and a semicircle with radiating lines stands for “sun.” The geometric environment surrounding these forms seems more of an interior than an exterior. I wonder whether this configuration reflects a fantasy of the landscape experienced from within an interior setting, or even from the “interior” that we experience as mind—a reality seldom depicted. The immediacy I associate with Federle’s art stems from his sustained contact of mind with sensation and feeling.

An array of black bars on an atmospheric ground, seen in Crash in the Mountains (1977)[7], an acrylic on paper, suggests a debris field, something broken apart. I asked Federle about the nature of this “crash,” whether the image alluded to an avalanche, an airplane, or a mountain climber. He replied that he was thinking of the risk inherent in climbing; the death or disintegration was not only of the body but also of a life’s convictions and goals, all gone to pieces. Convictions and goals belong to the mind, the spirit. When Federle draws, the object is mind as much as matter or body. His thoughts on climbing are poetic, and his images express these sentiments better than would words. His meanings are not specific, he says, but vaguely psychological—matters of feeling. Such emotional conditions remain nonverbal and unnamed. Federle represents the ineffable.

I’ve suggested that Federle’s geometry of mountains hovers on the edge of abstraction and representation. In the context of his environmental risks, the watercolor 4 Forms (1976)[8] seems to represent something fragmented, another case of breaking apart. The watercolor Modern Mountains I (1976)[9] and an untitled drawing in watercolor and pencil (1976)[10] suggest landscapes of mountains that are more fragmentary than integrated. Given the situation of contemporary art during the 1970s, Federle might have been playing with introducing representational values to an era dominated by abstraction (he mentions his interest in the mountains of his Swiss predecessor Ferdinand Hodler).

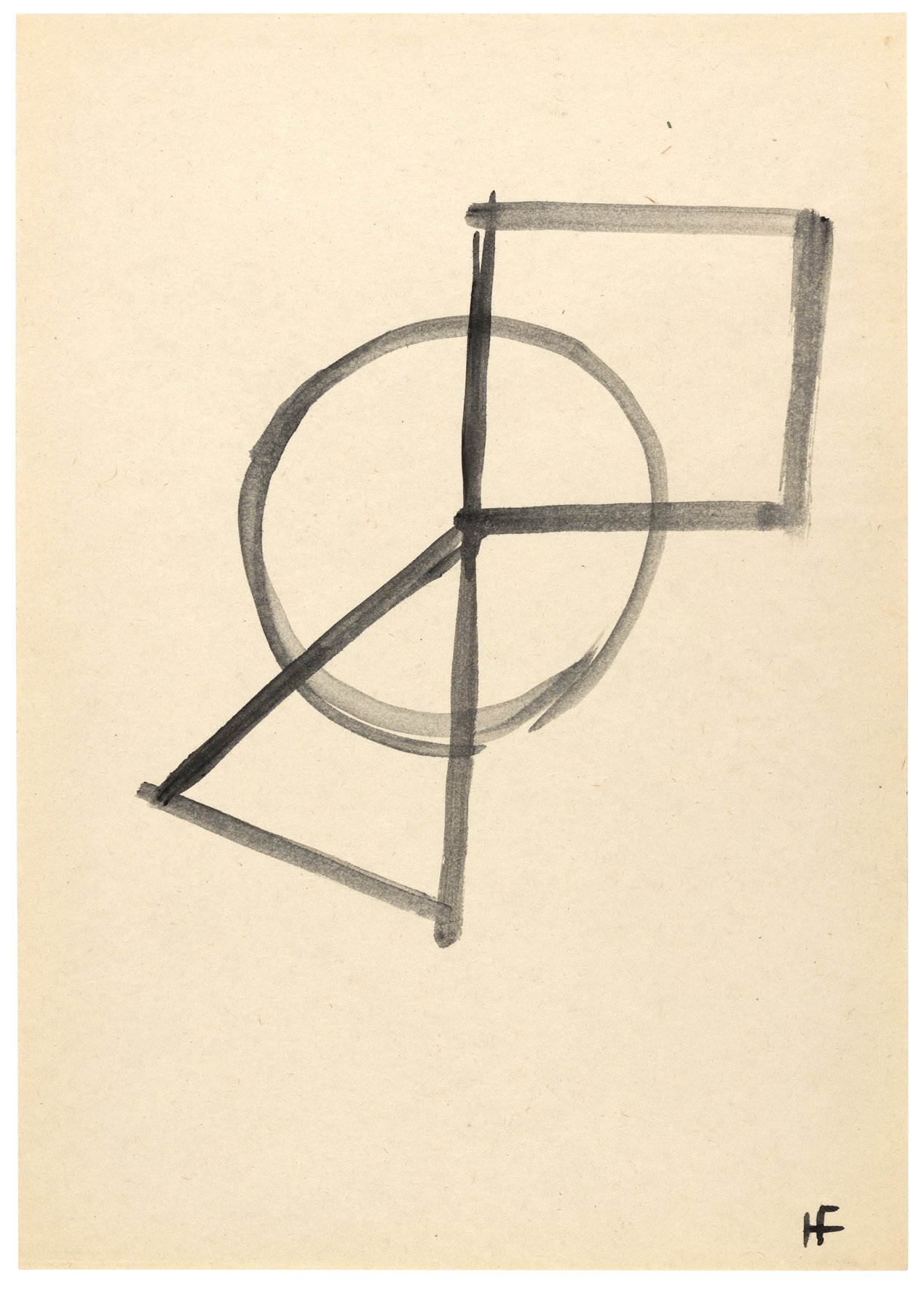

Geometry can be derived from both mathematical abstraction and naturalistic representation. The remarkable pencil and ink drawing titled Flower (NYC) (1979)[11] manifests this type of ambivalence; it superimposes two geometrical orders, each with five facets, to evoke an organic form that could be a flower or even an architectural structure, some advanced type of ribbed vaulting. Or it could merely be a geometer’s fantasy, with no reference intended. One of Federle’s drawings, an untitled watercolor (1979)[12], may indeed be such a fantasy; it orients the angles of a square and a triangle to the center of a circle, configuring three fundamental geometrical concepts as a single vision.

Federle’s drawings reveal the mind’s capacity to condense lived experience into a compacted image. This is the immediacy of his art. Several moments become one. An untitled work in acrylic and pencil evokes a range of mountains simply by introducing a contrast of angled dark and light in the top register of the sheet (1976)[13]. Along the slope or base of these “mountains,” a set of four linear elements suggests a “fall” from vertical to horizontal, a fall to pieces, a “crash.” The image projects emotion, a sense of the insecurity, the contingency, inherent in passing from one moment in a life to the next—the risk perceived in tracking a line while drawing it. A line alters the totality in ways that the hand never fully controls.

As a student during the late 1960s, a few years before he made these drawings, Federle was impressed by examples of recent American art that he viewed in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel, especially the oversize paintings by Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still: “I learned that the value is spiritual, and not formal.” Federle had sensed the openness of these works, the recognition on the part of the artists that their art would speak back to them in an immediate dialogue. This was its “spiritual” quality, beyond its material presence. In contrast, “formal” art was an art of control, for which the artist had an advance plan or method, which divided thinking from making or acting—one-way art, not two-way.

Federle rejected formal art, understanding that it entailed no risk. He became the spiritual climber, always subject to a fall, aware that by allowing his thinking and sensing to be in immediate correspondence, he would be placing his immediate future at risk.

Richard Shiff is the Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art, and Director, Center for the Study of Modernism, at the University of Texas at Austin.